Our History

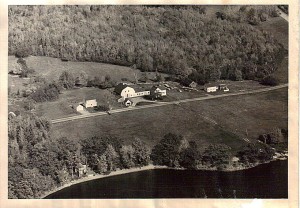

Located in a beautiful setting at Fields Pond in rural Orrington, Maine, The Curran Homestead is a turn-of-the-twentieth-century living history farm and museum. Its current status as a non-profit entity is the result of the wishes of the late Mary Catherine Curran, whose family operated a subsistence farm with a dairy, poultry flock, vegetable crops, and a large woodlot that provided income to cover necessities. Alfred Curran, who predeceased his sister by five weeks, had owned the farm with his brothers since the time of their father’s death in 1941;  he and his brothers often found employment off the farm. Catherine worked for the Bangor Telephone Company for much of her adult life, and Alfred is known to have been a frequent “jobber,” in addition to running a dairy and firewood business, doing service-in-kind on Orrington roads to meet the farm’s property taxes, and intermittent work on the Maine Central Railroad. Among the five children of the Curran household, Frank was the only one to marry, have children, and seek a life off the farm as the eventual administrative head of Eastern Maine Medical Center. In 1959, a separate modern home adjacent to the western side of the main barn was constructed for Catherine to live in, and this structure still stands but is privately owned. It would be Alfred and Catherine who would eventually survive their siblings and decide the future fate of the farm together. When Miss Curran died in 1991, having recently acquired ownership, her will directed a portion of the homestead to be preserved in its original form.

he and his brothers often found employment off the farm. Catherine worked for the Bangor Telephone Company for much of her adult life, and Alfred is known to have been a frequent “jobber,” in addition to running a dairy and firewood business, doing service-in-kind on Orrington roads to meet the farm’s property taxes, and intermittent work on the Maine Central Railroad. Among the five children of the Curran household, Frank was the only one to marry, have children, and seek a life off the farm as the eventual administrative head of Eastern Maine Medical Center. In 1959, a separate modern home adjacent to the western side of the main barn was constructed for Catherine to live in, and this structure still stands but is privately owned. It would be Alfred and Catherine who would eventually survive their siblings and decide the future fate of the farm together. When Miss Curran died in 1991, having recently acquired ownership, her will directed a portion of the homestead to be preserved in its original form.

The Curran Homestead, Incorporated Steering Committee proposed the creation of a living history farm and museum incorporating the house, barn, and related buildings on 31 acres. Much of the original equipment, furnishings, and tools extant were either donated to another nearby museum, or sold at the estate auction shortly after Catherine Curran’s death — and before the incorporation of the non-profit living history farm and museum. The remainder of the acreage of the original farm on the opposite side of the road, including a pond and island, was donated to the Maine Audubon Society as they had proposed to make use of the land as a bird and wildlife sanctuary.

The present Curran Homestead includes the original seven buildings from the time of the Currans: the barn, the main house, the Peter Field house, the ell, a small livestock building, utility building, and a heavy equipment building. Recently, two new structures were added. There is a smithy and a garden shed, and the first of these was funded by a grant from the Maine State Archives and the other by Home Depot. Volunteers were responsible for the construction of the buildings.

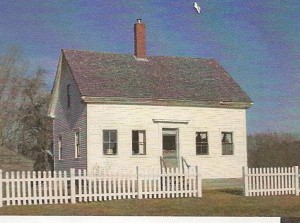

The Peter Field house has generally been thought to be the original farmhouse on the property. It was built in the mid-19th century, presumably by Peter Field, who purchased the land in 1804. Although the small, two-story house has undergone much renovation since that time, hiding and erasing much of its early character, including a large chimney and central cooking hearth appropriate to the time, there are signs of its early construction in the basement and on the second floor. These include some hand-hewn beams and early plastering visible in wall cavities on the second floor. The existing structure is more likely the last of a series of dwellings constructed by the Fields; earlier dwellings were likely torn down and new structures built in their place.

The Peter Field house has generally been thought to be the original farmhouse on the property. It was built in the mid-19th century, presumably by Peter Field, who purchased the land in 1804. Although the small, two-story house has undergone much renovation since that time, hiding and erasing much of its early character, including a large chimney and central cooking hearth appropriate to the time, there are signs of its early construction in the basement and on the second floor. These include some hand-hewn beams and early plastering visible in wall cavities on the second floor. The existing structure is more likely the last of a series of dwellings constructed by the Fields; earlier dwellings were likely torn down and new structures built in their place.

The main and larger farmhouse on the site was inhabited by the Currans since the time of their move, with their father M.J. Curran, from the nearby city of Bangor. The impetus for this was presumably their mother’s death and a more suitable situation to raise five children. The farm had been briefly owned by Arthur Conquest, whose son Edward had presumably been responsible for the purchase, believing that a horse farm would be a suitable situation for his father to retire to. Arthur Conquest had immigrated from England early in life. The extended Curran family, who originated in Ireland in the 1830s, had actually owned and worked farmland in Orrington since shortly after their immigration, so the Currans of Field’s Pond Road were third-generation Americans by the early 20th century.

The Curran house is a good example of a modest rural Maine farm family home with its large kitchen, equipped with a circa 1930 Glenwood combination gas and wood burning stove with a nearby hot water tank that was once plumbed to it, and an oaken ice box, adjacent pantry with a large working circa 1940s single basin farmer’s sink, examples of painted linoleum area floor covers, and double front rooms downstairs with a handmade glassed china closet with drawers, mirrored sideboard, treadle sewing machine, working reed organ and other furnishings. The core of the farmhouse may have been built as early as the 1860s, but it has been added to and remodeled as recently as the 1950s by the Currans; the living room and an additional upstairs bedroom and bathroom were added at that time. Housed within all of these buildings and on the property is an ever-growing through charitable donations collection of domestic items and furnishings, farm machinery, hand tools, and other accoutrements from rural Maine farm life dating from the mid-nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth century.

Unlike much of the rest of the country, rural Maine continued age-old agricultural practices long after other areas had modernized. Work horses are still used in the Maine woods by some loggers to this day, and the small dairy farmer found the pace of a single or team of horses suitable to the small fields defined centuries before by stone walls — in some cases until the 1970s. Certainly, the earliest tractors of the mechanized era remained in service long after they had been scrapped or abandoned in other regions. These phenomena were certainly the product of a relatively small state population and modest economic circumstances, and this is a focus of our mission, for we celebrate these circumstances which ultimately resulted in a regional culture characterized by thrift, self-reliance, Yankee ingenuity, and persistence.

A Curran Homestead Memory, by Earle L. Aucoin

(Transcribed from a typewritten account)

I have a memory of the Currans going back to the 1930s when, as a family, they would attend services at St. Theresa’s Church in South Brewer. One by one they passed on. The Currans generously remembered the Church in their wills.

Al Curran and I exchanged greetings for many years. I knew him from my high school days when I would help my father cut wood for him. Al was the scaler and payer. In the 1930s my father, Eyves “Jack” Aucoin, cut cord wood on the Curran woodlot in behind Copeland Hill. His day’s work was putting up two cords of hardwood, 4-foot length, split and piled. The pay was $4.00 a cord. The tools then were a wood-frame homemade bucksaw (the blade kept taut by twisting ropes), a 3½-lb. axe, and splitting wedges. It didn’t take long to “warm up,” and I remember rolling up my sleeves, even on below-freezing days. If we got our two cords early, we would have time for an hour’s hunt before dark.

Roads had to be swamped so that Al, or someone with horses, could sled the wood out to [the] roadside. Some of this wood was hauled to the Curran Farm via the old road. That road ran through the woods beginning where the Museum now sits, up the hill to the corner where the Hart Farm is located. At times there would be many cords, neatly piled in rows, in the valley behind what is now the Coral Johnson home. In those days there was no habitation from the Hart Farm to the Copeland Farm on the hill. That was the end of the road.

There was a very old camp on the woodlot. It was reached by a trail that began in the valley and curved around the hill — about a half mile. There was a spring nearby, and the usual outdoor “convenience.” My father stayed at this camp while cutting wood. In the Fall I would join him when I could. Mice were plentiful inside the camp, and there would have been many more if it hadn’t been for a somewhat tame white weasel living with us. Better than a cat!

One very cold morning I remember my dad starting a roaring fire. While he was outside, the old stove and smoke pipe got red hot. I was still in the bunk waiting for things to warm up. They sure did — the roof caught fire where the smoke pipe went through. Luckily, there was a pan of water warming, and that served as the extinguisher. The pail of water at the sink was still frozen over.

One Thanksgiving weekend I’ll never forget. It snowed for two or three days, and we were snowbound. The first day I went hunting on the snow and was soon chasing deer tracks. It snowed all day, and there was at least a foot of it when I realized it was getting dark. I broke off the chase and began backtracking. I found that my earlier tracks had filled in with snow. I was no longer able to follow them. Nothing around me looked familiar. There was no sound except for falling snow. The camp was lost. It was getting darker, and I had miles to go. I did have a compass with a luminous arrow. With the help of waterproof matches, I could see the dial. At around 8:00 PM, I saw the lamp shining through the camp window; I was elated. My father let on like nothing had happened, but we both knew how lucky I had been. He had fired signal shots from his rifle earlier in the evening, but I was too far away to hear them.

It snowed for another day or more, and there must have been two or three feet of the stuff. We couldn’t head for home as usual on Saturday. On Sunday, Dad fashioned snowshoes from spruce boughs, boards, and rope. These didn’t work too well, and we resorted to wading through waist-high drifts. Finally on Sunday afternoon, we were out of the woods and down the Copeland Hill Road to the Wiswell Road intersection. The road from Brewer had been opened to that point. We were some thankful to see my Uncle Amos Willett waiting for us in his 1937 Plymouth. He said he figured we’d show up sometime.

Our home was on McKinley Avenue in Orrington. We never owned an auto. It was a 6½-mile hike from home to the camp. My father would leave before daylight on Monday with a week’s supply of food in his knapsack and return Saturday night. I would leave home Friday afternoon for a night’s stay. Mother would have fresh bread and molasses cookies to carry in.

Once in a while we would get a lift in the 1937 Plymouth. These were the good old days when life and its pleasures were sincerely appreciated. I thank the Currans for the use of their property years ago. Did I ever get a deer there? Yes, several, but not until returning from World War II in 1946.

— Earle L. Aucoin, 10 March 2000